You Can Write Through It

Words as a path through chaos

Author’s Note: Another one from the archives. If you’re keen on reading more of them, in fact, you can always pop on over to Medium (if you have an account) and see them there. I’ve got several new articles in the pipeline and should have them out soon. For now, this one should be new to many of you, and I hope that you find in it something worthwhile.

First, you write for yourself always, to make sense of experience and the world around you. Our stories, our books, our films are how we cope with the random trauma-inducing chaos of life as it plays. — Bruce Springsteen

At 7:00pm on December 5th, 2021, I crossed the border into Tijuana with nothing more than a backpack and the vague outline of a plan. I had two changes of clothes, toiletries, several empty notebooks, and a clunky ASUS laptop that I would almost immediately become dependent on in ways that I couldn’t yet appreciate.

I had no goal except to wander. My only plan was: Cross the border, call an Uber, get to my hotel, figure it out. I repeated that mantra as I walked the anxious path to security. The sun was already down.

Cross border, call Uber. Cross and call, I chanted. Cross and call. Simple. I continued my chant until I got to the other side, where my phone signal promptly died.

I hadn’t planned for that.

Suddenly I was stuck on a dark street in northern Tijuana, surrounded by strangers. I couldn’t make sense of the bustle, and had no clue how to ask. It wasn’t quite a crisis? I was sure that many people knew English, but I didn’t know who. The uncertainty locked me in place as I tried to figure out how to proceed.

I could text, at least. I texted my brother, who gently reminded me not to be stupid. Too late, I responded. But as we talked I regained some confidence.

Okay, I told myself. You can’t talk well. So look. Listen. I recalled a lesson from my father — one he was fond of saying when I asked stupid questions. Look with your eyes, not with your mouth. So I looked.

The bustle slowly became legible: Here, a loading bay where people were meeting their families to catch a ride. There, a policia, talking with some pedestrians.

And there? Taxis. Several lines, haphazard, in a crush of colors. One line looked more official than the others — a row of white and green cars matched by a longer row of pedestrians. I joined the line, hoping that they would accept dollars in lieu of pesos.

Within a half hour I was at my hotel.

That evening set the tone for my walkabout. There are many English speakers in Mexico but I regularly found myself navigating unfamiliar situations without the crutch of conversation. It forced a different way of thinking — less compulsive, more attentive — and my notebooks quickly filled with details I would have missed if I had been able to talk more.

The experience gave me opportunities to meditate on the place of words in my life. I found myself contemplating strange questions — what would it be like if I lost words completely? What would I lose? Or gain?

It was clear that when I couldn’t lean on talking I paid closer attention to the world. Familiar rituals like buying bread became strange when I couldn’t work my way through small cultural permutations by talking. I had to carefully watch people’s actions.

At the same time, many of my impressions and observations only became clear when I put them to words while describing them to friends and family. I began to appreciate Steven Pinker’s injunction that words cleave the air, carving the chaos of experience at its joints.

Joints are a curiously appropriate metaphor. Joints are also called articulations. That’s what we are doing when we name the world — making joints in it, articulating it, so that it becomes tractable.

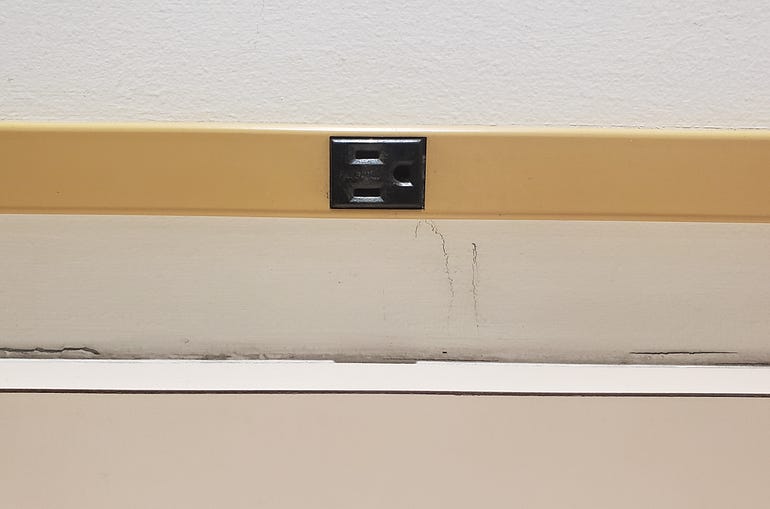

Words accomplish that by limiting. If I say “light socket,” I am conveying a rough map of a light socket’s form and function. It has holes. You put a plug in it. It turns on your lamp. Further nuance is lost.

Want proof? Picture a light socket, would you? Good. Now, did you see this?

Probably not. Odds are that you pictured a two-plug, comfortably taupe socket like the ones in your house. The above picture is also a socket but the details — its sideways-ness, or the fact that it is mounted in an orange strip — disappear. You get the gist though, so if I say “Could you plug my computer into that light socket near you?” you know what to do.

Words cut through variation to the stable core of an idea. Much is lost in the cutting — the sideways-ness of this light socket, the smoky undertone of that cup of coffee, or the strange and nevernamed quality of light in that particular rainbow, which you will only see once, ever — those things vanish and can only be summoned with different words. Sometimes there are no words for them at all.

But also, much is gained. Words remove detail but add clarity and reveal paths of action. They take the longing for home and a crush of subtle social norms and the bustle of a thousand engines in a town square and turn it into “Excuse me, sir, is this where I wait in line for the taxi?” By simplifying our experience they allow us to carve direction and agreement into chaos.

This principle matters for mental health. The mind is noisy but if you attend carefully to the noise you will realize that a lot of it isn’t words. A lot of it is un-voiced — urges, compulsions, and associations emerging in chaotic sequences that we struggle to understand and rarely investigate.

Many of the great therapeutic traditions leverage the simplifying properties of words to cut through this chaos. Two examples:

In mindfulness practice, naming is often used as a technique to help control thought. For example, rather than raging, a practitioner might name their anger by identifying it, saying “I’m feeling angry, right now.”

This shift from experiencing a pattern to describing it is a powerful way to get control. You don’t even have to describe it; a literal name is enough to identify and work with it. Years ago when I first started meditating on a candle flame I noticed a recurring pattern that distracted me constantly — it was an inarticulate bubble of misery, rooted in depression, that would surge and crest in waves of doleful protest, more groan than monologue.

I named it “Bob.”

Whenever Bob popped by I greeted him (“Hi, Bob!”) and invited him to watch the fire with me. And then Bob and I would sit there watching the candle flame together. Over time Bob started to grumble more about candles than agony. It was very strange, but surprisingly effective.A similar principle is at play in therapy. In the 1970’s Mary Lee Smith and Gene Glass of the University of Colorado, Boulder, published the very first example of a new type of research — a meta-analysis — showing that therapy worked.

They also asked which type of therapy was most effective. To their surprise, their data showed that the specific type of therapy didn’t matter. Why? One possibility is that most therapies require a person to sort through the undifferentiated thought-mess of their own history, putting words to it. The newfound clarity gives a person goals, principles, techniques, and an astounding release of psychological tension. This is echoed by later scientists like James Pennebaker, who found that the simple act of journaling was enough to help people better process the grief of losing loved ones.

Words have power, provided that you are putting them to their best use. It is true that words can be used to deceive and abuse, but at the structural level words serve the purpose of finding the common core across disparate experiences and attaching a joint to it so that we can use it to build bridges to others.

This is a superpower, a human superpower. Scientists often speculate about some factor — like fire, or brutality, or trade — that helped humans climb the evolutionary ladder, but none of those even work without words. Words took fire and turned it into replicable instructions for tempered steel, took violence and turned it into law and punishment, and took cavemen swapping furs and turned it into economics. Words build in a way no other human quality can reach.

And for you? One of the most potent tools you have for promoting your own mental health is the keyboard or pen sitting right in front of you.

Writing won’t solve every problem you have — in the end, you have to couple thought with action to get anywhere, and some problems (like depression) are so deeply systemic that it is difficult to get them to budge at all, using any technique.

But writing can help you charge into the tangled parts of your soul and un-tangle them. If you struggle with the future — if all you feel about it is bursts of dissatisfaction that fail to point you in a useful direction — writing can help you figure out if there’s a path, where it is, and where it leads.

If you struggle with waves of melancholy or fear, try describing them — articulate when and where they happen, and what you think about when they do. Ask what they point to, and then wander that way and try to articulate that too.

This is not an easy practice — periodically I have stumbled across insights in my own writing that reduced me to tears.

But even if it’s not easy, it is effective. Do it often enough and the knot will unravel. It may not be pretty, but when it’s done you’ll be left with a bright, golden string to help you navigate the labyrinth, and to mark your way home.

"James Pennebaker, who found that the simple act of journaling was enough to help people better process the grief of losing loved ones."

He also found that journaling boosted the immune system!

I recall being impressed when the "narrative" paradigm of psychotherapy appeared, arguing that people get "better" by editing their personal "stories" into a form with more coherence and meaning and self-validation and hope. Words matter.

Good writing, James. 👏

You have a good sense of language and metaphor. Thanks for articulating all this, and bringing that word back to life for us. I will remember also “look with your eyes, not your mouth.” 😆